Feature Photo used under Creative Commons license courtesy Paxson Woelber, The Alaska Landmine

What Are We Talking About?

Americans are entrusted to 640+ million acres of public land. Most of the time you can simply google what public land is near you (National Parks, National Forests, State Parks, BLM lands, Wilderness Areas, etc.) and look up some trails or areas to go hiking, camping, hunting, kayaking, fishing, or any other recreational activity allowed in the area.

But a lot of America’s public lands cannot be accessed by the the public. This is currently the case for nearly 15 million acres of public land (about the size of South Carolina) which has become landlocked through a long and complicated history of land acquisitions, transfers, sales, and other means.

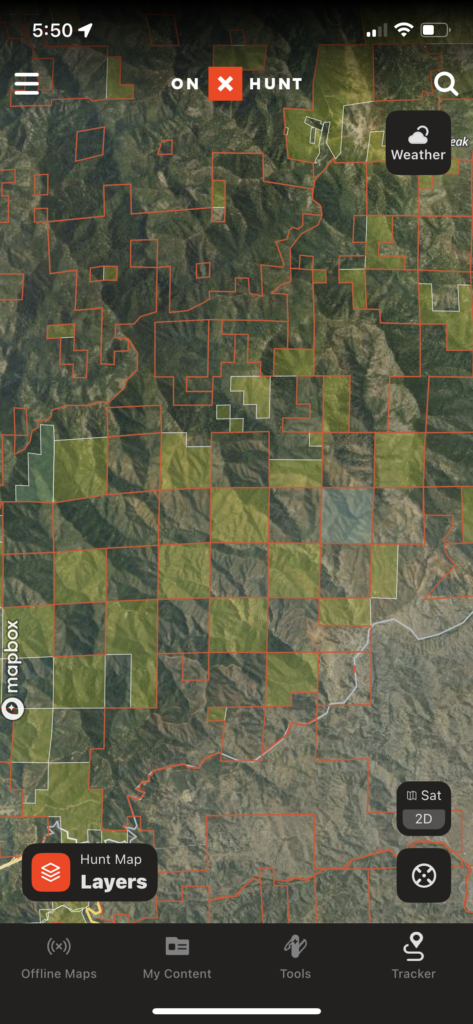

This means that when the public (you or I) tries to access this land via the officially established trails, roads, waterways and other access points, you may run into a literal block: “Private Property” signs, “No Trespassing” signs, fences, gates, and other restrictions. Not something you may expect to see on what is indicated as a publicly available trail. Some of this public land is isolated like an island in a sea of private land, and some of it inaccessible due to a checkerboard pattern of public and private land parcels of which the corners are illegal to cross. And these are not just minor patches of land. They can encompass thousands of acres which would otherwise be used by the public. Here is a visual to illustrate exactly what this looks like:

Inside the red borders are privately owned lands. The moss green areas are public lands. As you can see, several of the BLM lands are surrounded by and landlocked by private lands, making them inaccessible to the public.

An example of the checkerboard pattern of private/public land that has occurred over America’s history of land management. Corner crossing is illegal, making many of these public lands inaccessible to the public.

This issue was largely brought to the masses attention due to the OnX app – a popular hunting app that displays detailed maps of public lands, private lands, and approved hunting areas. Over the years their data combined with the help of other major conservation organizations began to reveal just how much public land has become inaccessible to the public.

So has all this land been maliciously blocked from the public in pursuit of privatization and personal gains? In some cases, sure. After all, this nation has a strong foundation and disposition for a free-market economy and Adam Smith economics, and when that applies to property that intersects with public land, it results in quite a controversy. But not every private land owner is an adversary of public lands, either. As with many things, it was a complicated series of events on how we got to this point, and still is. And ultimately, unlocking public lands does not mean private property owners have to give up their property rights. The general approach among these organizations and efforts to unlock public lands is to work with private property owners and not pin them as direct adversaries. No matter which way you cut it addressing the patchwork of fragmented public and private lands will be critical for the future of America’s public land system and wildlife conservation efforts.

What Is At Stake For The Public And Private Sectors?

Public land users

Roughly 7 out of 10 people in the United States live within 100 miles of public land. This is great in principle, considering not everyone has the ability or luxury to own a large plot of land with which they can enjoy at their private discretion. But as more of this land becomes inaccessible to the public, it loses that value. It may be hard to empathize with this if you personally have good access to public land, but this is a reality that many people are facing today. Outdoor enthusiasts are unable to hike, camp, and backpack into wilderness areas to enjoy the benefits of nature or share those experiences with their loved ones, families, and friends – transformative life experiences. Hunters and anglers are less able to sustain themselves off the land, resorting to grocery store factory farmed meat instead of wild game.

Jobs and economic opportunities for rural communities are also lost as they may depend on access to public lands. This includes outdoor recreation services like guided rafting trips, hunting and fishing tours, camping outfitters, as well as jobs in natural resource management such as timber and water management. Should a private land owner decide to remove access to a public road or trail they can create a monopoly over the public land by establishing premium, private outdoor experiences that are only available through them, reducing the benefits of those recreational services from entire community to just a single land owner.

Eventually, these exclusive experiences – golf resorts, luxury ranches, glamping – can drive up the value of the land around them which will price out the middle and lower class citizens. No more single story homes or affordable cabins for the communities near these public lands. Only luxury cabins and developments for wealthier individuals that can afford the privilege of hiring the private outdoor guides to give them exclusive access to what should be public land. Great progress for some in a market economy, but a challenge for others. In effect, these areas maintain the label “public land” but in reality become privatized. It defeats the many purposes of “Public Land.”

A current example of this in the Crazy Mountains of Montana where public access to trails and roads are continually blocked and wrapped in a land-use rights battle between private land owners and the general public. Once easily accessible from multiple points, over 22,000 acres of land in the Crazy Mountains have been reduced to a just a few access points. This land has since gone through negotiations for consolidation and transfer between private and public owners, but not without significant concessions. For an extensive look at this issue, check out How To Privatize A Mountain by Joseph Bullington.

Private land owners

If I am being honest I would personally love to own some land that borders a National Forest or another one of our beautiful public lands. But that comes with the responsibility of being a good steward of the land, while also understanding public access needs in conjunction with your private endeavors. For better or worse this is also part of America’s identity – independence and self sustenance off the land. Not all private land owners are out to dismantle access to public lands. And if we are all being honest, we know not all public recreators are angels themselves and can be quite destructive to the land.

I do not propose to know every possible motive of private land owners who are near public lands, but let us consider some of the benevolent personas. This can include families who historically claimed this land from homesteading over 150 years ago before the surrounding areas were designated as public lands, serving as good stewards of the land and surrounding wildlife. It also includes any other person who has worked their entire life, has a passion for the outdoors, and now they can finally afford a cabin on or near their favorite public land where they can hunt, fish, and access the beautiful outdoors with their friends and family. And as we have learned, much of this private land may intersect with or overlap potential access points, roads, and trails for the public.

Through permission, land transfers, easements, and other means, many land owners are more than obliging to allow for the public to hike through their property to access public land. For example, to access certain areas of the Chicago Basin in Colorado – one of most spectacular areas for hiking and camping in the country – you will need to cross through some private land. Currently, the land owners allow outdoor recreationalists to take a trail through private property into the wilderness beyond, and in exchange the public should not cross over the private boundaries or do any damage. That is a fair ask, especially considering that many outdoor recreators can unfortunately horrible stewards and do not respect the land. They leave trash, they are loud, do not bury human waste, cut trails and create erosion, burn fires when they should not, hunt and kill wantonly, and do not follow the basic etiquette of being outdoors.

This can leave certain private land owners with a bad taste in their mouths. For example in many States the rivers, streams, and waterways are owned by the State or federal government and are open to the public. This includes the fish, the rocks, and anything that is in the water. Now, let’s say someone buys a large plot of land – 500 acres, that is on either side of a popular trout fishing river. Although they own land running against the river, the public can still access the actual river running up against that land to use for recreation. Or take an established trail that now runs through the recently purchased private land. Through historical usage the public still has a right to access this trail. But it should be no surprise if private land owners restrict access to these areas with a gate or fence should the public be completely disrespectful of the land and surrounding property.

Of course, not all private land owners who border public lands are benevolent or good stewards themselves. Many wish to retain this land for themselves and no one else, privatizing the land around them by creating an outfitter company that has exclusive access to a prime hunting grounds on a section of National Forest. They may sell this land to developers for commercial zones, resorts, or other private institutions strictly for monetary gain. Others will sell to extraction industries, just as the Singer Corporation did with their forest land in Louisiana in 1937 which resulted in the felling of ancient hardwood trees that supported the last population of the ivory billed woodpecker (now extinct).

Collateral damage

Blocking access to public lands – both federal and state – creates challenges for wildlife populations, natural resource management like clean air and water, and risk mitigation for floods, wildfires, and other natural disasters. Things as seemingly benign as fences can completely isolate populations, such as wild antelope who have literally not evolved to jump over fences and are unable to do so. Of course, many private property owners do provide corridors and paths for animals, and participate in activities to manage resources and mitigate natural disasters. And although now a more accepted and understood method for wildfire prevention, private land owners are not required to use prescribed burning on their land, and can be reluctant to do so. Reportedly this is because the land owners are at risk of litigation and bankruptcy should any fire escape the prescribed area and burn elsewhere, and because insurance companies no longer cover these claims. Altogether this challenge of landlocked public lands makes managing wildlife, natural resources, and natural disasters a challenge for private land owners and other managing agencies.

How Did This Public Land Get Locked Up In The First Place?

So how does this land – an established part of America’s public land system – end up out of reach to the public? The answer is complicated, as America’s land has gone through countless battles for access and rights of use, and the forcible removal of natives, deed transfers, private purchases, land grants to corporations, easements (or lack thereof), and other complicated handlings. This has led to some major achievements in modern day wildlife conservation and public benefits, but has also resulted in a complicated smattering of land parcels and fractured landscapes.

Beginning in 1783 and throughout the next century, America amassed its land from other colonial powers and native populations. As they did, they needed to survey this land and organize it for future sales, settling, and other national needs. This started with the creation of the Public Land Survey System in 1785 which developed a method literally known as the Rectangular Survey Method in which all of our land was surveyed and divided into neat little 1 square mile parcels (640 acres). Now, the government could more effectively portion off this land to public and private buyers.

These sales and deed transfers were accelerated with the Homestead Act of 1862 and the Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862 & 1864, used to subsidize families to populate the new territories out west and to subsidize the building of the transcontinental railway, respectively. With The Homestead Act settlers were granted 0.25 parcels of land (160) acres out west to claim as their own and establish a farm or homestead for a small filing fee and minimum 5 years of residence. The Pacific Railroad Act incentivized rail companies to build the transcontinental railway by providing them with every other parcel of land along the rail lines (this is what has created the checkerboard patchwork of land which plagues public land users today). Rail companies could use this land as security holdings, ultimately selling it to land and oil spectators, farmers, and other individuals or enterprises to raise capital and finance the building of the railway. What would the federal government do with the other adjacent parcels of land that was not offered to the rail companies? Well, they hoped to sell these at a later date under the assumption that they would later increase in value based on other towns and industries establishing themselves along the railways. This was not always the case as much of the arable and valuable land was already taken up, so this land sat for quite some time.

Very quickly America’s land was being sold and privatized, and by 1900 most of the land holdings that remained from rail companies and the federal government were west of the Rockies (hence why the west coast of the US has far more public lands than most of the eastern states). The very thing that attracted people to America in the first place – the immense wildlife, and endless land – was dwindling away and taking America down the path of the old world (the UK) which had become a biological and ecological dead zone over the millennia.

Thankfully, Congress started to recognize this, seeing it was not only a threat to our ability as a nation to manage and protect natural resources, but it was a threat to our wildlife and natural areas. Now many of the land tracts America had once set aside for privatization became part of a new public domain, most notably with the creation of Americas first national park Yellowstone, in 1872 by removing 2 million acres of land from homesteading and private sales. Other prominent figures like Teddy Roosevelt were active proponents of this cause, forming the Boone and Crocket club in 1887 to campaign for establishing a better relationship with wildlife and the natural landscape. This attracted the attention of many other naturalists and politicians who saw the value of land reserved for wildlife, regulations around hunting, and land for use of the public domain, the most critical of which was John Lacey, a congressman from Iowa. Lacey’s greatest contribution and one of the most important moments for public land was the 1891 Forest Reserve Act, which removed 13 million acres of federal land from private sales and ultimately turned into our current day National Forest Service. Fast forward many years and you have the incredible public land system which you can explore today, saved from over privatization.

Between the homesteading, railways, sales, transfers, and then the creation of our public land system and National parks, you can see now how America’s neat little 1 square mile parcels became an oddly fragmented grid of public and private land that results in these islands of public lands or checkerboard patterns. As a note of interest, the Homestead Act was not actually repealed until 1976, except for a 10 year extension in Alaska. All this means is that land use, management, and access will continue to be a topic of great debate given America’s dual identities: One of extreme individualism and private enterprises, and one of wilderness exploration and self sustenance from the land.

How Is This Being Addressed Today?

Laws and policies have in effect to help address this issue for a long time. And today many grassroots organizations and policies continue improving access to public lands.

1964 – Land and Water Conservation Fund: This fund uses royalties from oil and gas development to fund public lands and conservation initiatives. The Land and Water Conservation Fund actually expired in 2016, was extended for a few years, and then expired again in 2018. But thankfully, it was re-opened in 2019 and then in 2020 the Great American Outdoors Act took over and permanently funded it, bringing back a very important initiative for the support of our public lands.

Land Access Initiative: Started by Steve Rinella, this initiative helps increase public access to our public lands. You can submit requests to review areas that are currently blocked which they will consider for their initiative, no matter how big or small the access point may be.

The Nature Conservancy: This organization provides tremendous support for expanding and unlocking public lands. This is often done by purchasing tracts of private lands that are for sale and opening them for public use and conservation, most recently purchasing 8,000 acres of land in a major delta and biological hot zone in Alabama.

2024 – BLM Public Lands Rule: Historically, the BLM has focused primarily on leasing their surface and sub-surface land to mining, extraction, and agricultural industries while putting less of a focus on conservation. This new rule establishes that wildlife conservation and public access will be safeguarded and prioritized with the same degree of importance as their leasing operations, leveling the playing field in how the land will be utilized. Being the largest public land manager (nearly 250 million acres), this is a big win for conservation and public land access.

There are many more key players than those mentioned above, and you can always find local organizations in your area. Find one and support them if you believe in our public land system.

Final Thoughts

Having a secure place to live and provide for your family is a basic human need. As I mentioned, I will (hopefully) own a property or home myself one day. However, deliberately limiting everyone else’s access to public lands via your private property has significant and unfair consequences to tax paying Americans who depend on those lands to be public. But as users of these public lands it is just as critical to remember that they are public, that it is a privilege to have them, and that they have a complicated history between the private and public sectors. Don’t pollute or damage property. Respect the land and everyone else who is using it.

Enjoy the journey – J. Wasko

About the author

Jeremy Wasko has been exploring our public lands for over two decades. With thousands of miles and hundreds of camping trips completed. Through his adventures, he discovered that our public lands are more than just places to camp and recreate. They are cultural and historical sites, sacred places to different peoples, and the very sources of our clean water, air, and other critical resources.

He created Magna Terra to share his knowledge on how to explore and enjoy our public lands, and also how to protect and conserve them for future generations.

Learn more about Jeremy and the founding of Magna Terra here.